Contents

Bert Hellinger: Thoughts of Peace

WORKING WITH THE COLLECTIVE

Annelieke Verkerk: Beyond Right and Wrong: A Societal Constellation on Polarisation

Nikki Mackay: Those who left and the Left Behind: A Liminal Space

HISTORY OF NATIONS, CULTURES & RELIGIONS

Veronica Bañuelos Miramontes: In Solidarity

Nikki Mackay: Voiceless Women – An Unspoken Legacy

NEW APPROACHES

Irmgard Rosa Maria Rauscher: Yoni Constellations

RESEARCH & DEVELOPMENT

PERSONAL REFLECTIONS

Josh Alexander: A call for the proper inclusion of Transgender People

BOOK REVIEW

Francesca Mason Boring: Learning Transgender from the Outside Looking In by Bertold Ulsamer

BOOK EXTRACT

Marine Sélénée: An Excerpt From: Connected Fates, Separate Destinies

Rafael Ruiz Mandal: Impotency & Hope

Angus Landman:

The Face of God

Because I love I Fly

One Knee on the Ground

Michal Golan: In the Service of Life: About Being a Representative

Editorial

After quite some time of sitting with the idea, I have finally decided to hang up my hat as Editor of The Knowing Field. The next issue in January 2023 will be my last. I am aware of a mixture of feelings about my decision, but it feels right.

It is not yet clear to me whether the journal simply needs to lay down its head or whether there is someone out there ready to pick up the baton and take the next step. Please contact me if you think you might be interested in this idea. It is a lot of hard work but the rewards are immense. There is such a richness of articles accumulated over the years that for the time being at least, I will keep the website open so people can continue to gain access to what’s there.

The cover image for this issue is designed to somehow convey the two paths ahead as my own personal path and that of the journal, as we go our different ways. Parting is indeed sweet sorrow.

So, to return to this issue, my first foray into finding something from Bert landed me on this piece about forgetting the dead and how they are generally more at peace when we do – after a time of grieving of course. Is it time for Bert too to be forgotten? Increasingly, new people coming into the field of constellations hear only stories of him, variable in their relating. I still remember him saying he didn’t want anything in writing because it would become dogma. In fact, I think this is actually written by Hunter Beaumont in the foreword of Love’s Hidden Symmetry. Ironically, Hellinger published more than 30 books with combined sales of one million copies in at least ten languages.

Even as he and his wise words are remembered, new directions in the work are taking place. Annelieke Verkerk brings the first article under our recently introduced heading of Working with the Collective. In it she describes the painful effects of polarisation, using the recently divisive event of vaccination against Covid-19 and through a constellation discovers underneath the vulnerability and fragility of life and an accompanying sadness. From it also come some possibilities for moving through the divide.

Next in this section is Nikki Mackay with her article on ‘Those who left and the left behind’ and she elucidates the deep pain involved on both sides with a constellation on the current troubles in Ukraine.

We have several articles in this issue on oppression. First of these, Veronica Bañuelos Miramontes describes under the History of Nations section the current plight of BIPOC (Black indigenous and people of colour) and the pain of not being met. She challenges us all to meet BIPOC in their pain, to stay present to their trauma and to become allies for them in their struggles to be fully seen and heard. This is an area within the constellations field, which still has a long way to go in terms of those of us who are white, fully facing the history of colonialism and how it is perpetuated currently in society.

Also coming under the theme of oppression, Nikki Mackay returns again in this section to address the past and present experience of women being voiceless in the wider field and the wounds involved in the struggle to be heard, plus the fear of speaking out. Interestingly, I am reminded of a sentence from a book I read recently on the emergence of women into their power and how within that movement, the plight of black women was overlooked. How hard it is when we ourselves belong to an oppressed group to, at the same time, be inclusive of other such groups.

We have a new development in this issue with Irmgard Rosa Maria Rauscher introducing Yoni Constellations and the importance for us as women in valuing the parts of our female body from which life first sprang and finding our power in that.

She too, describes the past oppression of women in their sexuality and the wounds for the feminine that emerged from that.

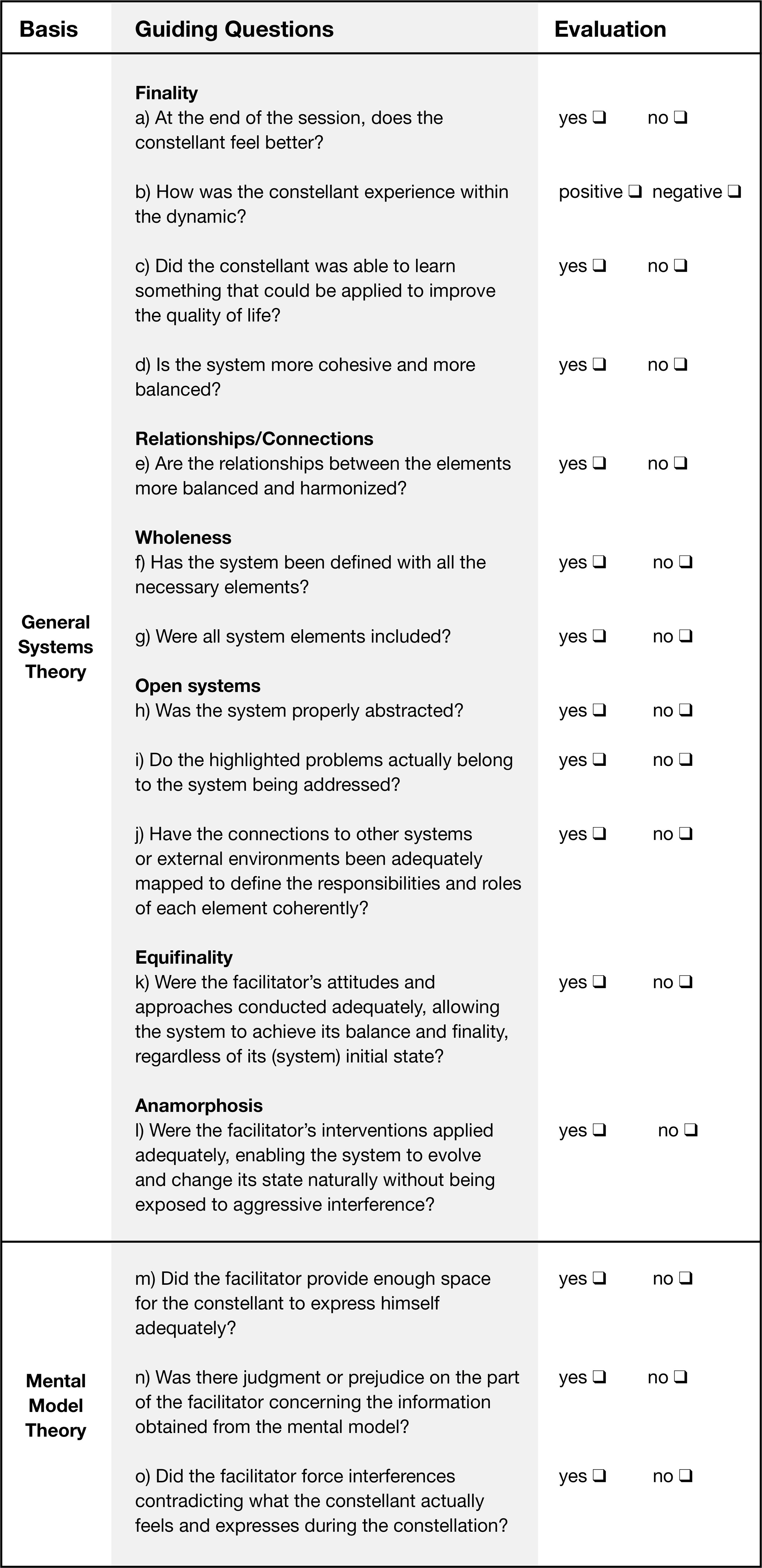

Simone Perazzoli and José Pedro de Santana Neto have generously offered us their research project into increased understanding of constellations. They acknowledge the input from other researchers and with the breadth of approaches within the field, what a complex and challenging initiative it is to undertake. Nonetheless, they make a thorough and valiant attempt at bringing greater understanding to the field, through the introduction of General Systems Theory and Mental Model Theory.

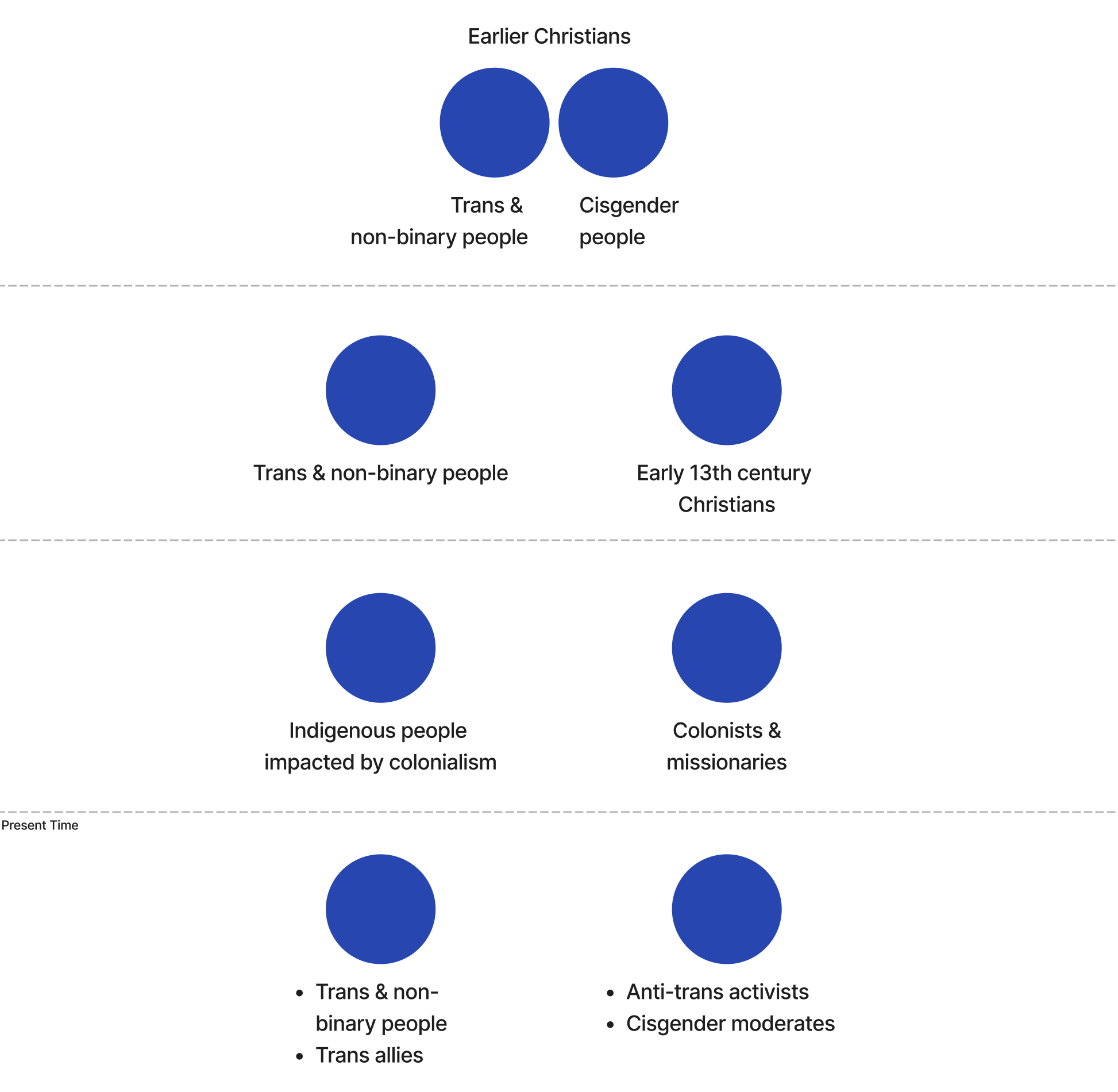

Under Personal Reflections, we have two inputs from Josh Alexander and Karen Carnabucci on the topic of LGBTQI, each coming from their own perspective. In reading both, it is easy to feel the pain on both sides and how important it is to be able to listen and learn from our painful experiences and at the same time to bring into the field more people from this much maligned and neglected section of society, so we can become more open. Bertold Ulsamer helps with this by courageously writing a book on his own journey with this issue and his acknowledgement of his vulnerability and lack of exposure to the subject. Francesca Mason Boring beautifully describes this in her review of the book.

Marine Sélénée’s extract from Connected Fates, Separate Destinies, Chapter 5 challenges us to say ‘Yes’, to our partners, to our partner’s family and to ourselves exactly as we are and to our own destiny. She sees this as the way forward for each of us if we are to find true inner peace.

Finally, we have some really beautiful poems from our regular contributor Angus Landman, from Rafael Ruiz Mandal and newcomer Michal Golan.

We are finally emerging from turbulent and difficult times over the past few years. Let’s hope the future holds more positive and health-giving gifts for each of us. It can be helpful in such times to remind ourselves of all the people and things we have to be grateful for. Gratitude is a wonderful feeling.

My thanks as always to all contributors, advertisers, ‘Friends’, my graphic designer, Lubosh Cech, and editorial assistants Abi Eva and Francesca Mason Boring.

Barbara Morgan

Editor

Back to Top

Thoughts of Peace

Peace to the dead

Bert Hellinger

Most of the dead are at peace, and any concerns about them and any thoughts of them disturb their peace. They are beyond our world.

I have an image of life. Life is an interlude between what was before and what will be afterwards. Therefore the unborn and the accomplished are equally taken care of. If someone wants to get in touch with them, for instance because he or she wants to put something in order with them because he or she feels guilty towards them, the dead do not understand it.

But we also experience that some of the dead still have their effect on the present. They are not at peace yet. Sometimes they attach themselves to the living and draw them into death. These dead need help. It seems these dead do not realise that they are dead. They are still seeking nourishment from the living and suck them dry. To engage with them and give in to them is dangerous.

How can we escape them? We escape them in our pure existence. In their present, we dissolve as it were, into pure relating, so that nothing is left of us that they could attach themselves to. In this pure relating one is fully permeable, one looks away from them towards a mysterious dark, and then remains collected in its presence. This has the effect that the dead are also turning there, away from the living. We allow them to dissolve there, into something that Richard Wagner calls: Blissful primordial forgetting.

Where does peace begin? Where memory ends. The deepest longing in everything is the entering of this forgetting.

I went out on a limb here. What I am speaking of here is only to get a sense of which movements are possible and what effects they have in our soul and in the souls of others.

What is the worst for the dead? Remembering them. Not in the beginning, memory is still alive then. But dying is apparently a process of gradual release of oneself. This process, the process of releasing, should not be opposed. For instance, through memory.

The biography of a deceased interferes in this process. Every accusation, every complaint, every extended grief, interferes in this process.

A little while ago I opened a book to read something about the crusades. Suddenly I became aware that if I read on, I would get in the way of the peace between the perpetrators and the victims. Then I closed the book.

Forgetting is an aspect of the highest love.

Who among the dead fare best? Which ones have completed their dying and have eternal peace? Those whom we allow to be forgotten.

We can also imagine how it would be for us if we die and are remembered, or if we die and are forgotten. Where is the accomplishment?

After some time all the dead must be given the right to be forgotten.

Sometimes there is still something in the way. They expect of us that we respect them, that we perhaps still thank them and still grieve for them. Only then are they free from us and we from them.

(Taken from The Churches & their God. Hellinger Publications, 2013)

Photo: Broken tombstone, Murano island cemetery, Italy. artbyluce.com

Back to Top

Working With the Collective

Beyond Right and Wrong: A Societal Constellation on Polarisation

Annelieke Verkerk

Introduction

In society and in the public debate we are witnessing a growing tendency towards Polarisation. Vaccination, climate change, migration, racial issues and other political topics stir up strong emotional currents and give rise to heated debates and actions. Increasingly, these rifts run close to home and create divisions between brothers and sisters, in families and longstanding friendships. A friend who lives in the United States shared that at this time he cannot discuss politics, racial issues, climate change or vaccinations any more with his immediate family. During lockdown that meant playing lots of card games to avoid venturing into ‘dangerous territory’.

Recently I explored this polarisation tendency with a group of colleagues educated in systemic work, through setting up a Societal Constellation. A Societal Constellation is a way to make visible issues, dynamics and relationships in a societal field with the use of representatives. The process of constellating involves representatives bringing in relevant elements pertaining to the societal issue at hand. During the process representatives share what they experience.

What in particular motivated us, was the need to gain more insight into underlying themes and motives and find openings for more constructive conversations and ways of being. In this article I will paint a picture of how the actual Societal Constellation transpired, and highlight some insights that may have wider implications and open up new pathways.

We chose to constellate the societal theme of Polarisation in the context of the current vaccination debate and trusted that wider implications of the polarisation phenomenon as such would also reveal themselves in the process. As virtually everyone in our group identified with aspects of this theme, we decided to experiment with collectively holding the topic without assigning it to a specific case-giver.

The actual constellation

Upfront we identify Polarisation, those who are Pro-vaccine, those who are Anti-vaccine, those who are Indifferent and Money as elements to constellate, and acknowledge the option of bringing in other relevant elements as the constellation unfolds.

As Polarisation takes her place in the middle of the field, she initially feels very ungrounded and is looking for something to get her teeth into.

Money holds a broad overview and wants to dominate the field.

The Indifferent have a constricted throat and do not want to be seen, as being noticed feels very unsafe to them. They take position behind Polarisation.

Pro-vaccine shares being motivated by pure health concerns and feels charged and strong in taking a stand.

What becomes visible is a trauma field, where Polarisation displays a fight response, the Indifferent embody a flight response, and then the constellation freezes as initially nobody feels called to represent or bring in the Anti-vaccine element.

In the meantime a finch has flown into the room of one of the participants. It is quite a tender and vulnerable image, seeing this bird quietly settling in her hand. After a while another participant feels called to represent the Vulnerability of Life.

That breaks the constellation open: the Indifferent want to surrender to Vulnerability of Life, Pro-vaccine wants to really protect Vulnerability of Life, and Anti-vaccine now feels completely settled with Vulnerability of Life in the field.

Vulnerability of Life expresses that it is important that the voice of Anti-vaccine is also heard.

Pro-vaccine realises that, even though his motives feel pure, in helping he can also inadvertently cause hurt and overwhelm.

Money feels humbled.

And Polarisation expresses that experiencing the sadness in the field finally opens her ears so she can hear. This seems to be an important systemic sentence: “Sadness opens my ears so I can hear.”

Now the finch finally flies away into the sky and the person who held it feels called to represent a Portal, a doorway that opens into a bigger space.

Initially Polarisation thought that she was also contributing to the future. Now she realises that only together with Vulnerability of Life can she pass back and forth through the Portal, in and out of that bigger space, with expanded awareness – experiencing the polarities in the here and now and moving beyond the pro and anti. And as Portal points out: that is actually easier than you think.

Reflections and insights

The constellation reminded me of a line by Rumi: “Beyond ideas of wrongdoing and rightdoing there is a field. I will meet you there.”

When I looked up the poem in ‘The essential Rumi’ as translated by Coleman Barks, I was blown away by the analogy of what we had just experienced:

“Out beyond ideas of wrongdoing and rightdoing,

there is a field. I’ll meet you there.

When the soul lies down in that grass,

the world is too full to talk about.

Ideas, language, even the phrase “each other”

doesn’t make any sense.

The breeze at dawn has secrets to tell you.

Don’t go back to sleep.

You must ask for what you really want.

Don’t go back to sleep.

People are going back and forth across the doorsill

where the two worlds touch.

The door is round and open.

Don’t go back to sleep.”

Indeed two entrances into the same field.

Connecting with the vulnerability and fragility of life and the underlying sadness seems to be an important opening to being able to transcend the polarity of right and wrong and move conversations to a plane where people can see and hear each other again.

What would be the effect if we were to be more intentional about really meeting each other, seeing each other’s humanness and finding ways to keep conversations going?

Learning to be with others in a ‘here and now’ that encompasses past, present and future.

Holding both poles in the conversation – the black and the white – and learning to see and savour the rainbow of colours, flavours and possibilities in between, that have been present all along.

Practising and cultivating deep listening, beyond the words.

Exhibiting genuine interest and asking questions.

And connecting from our ‘shared humanity’, that heart-opening ‘next-level’ paradigm that unites and transcends, “consciously going back and forth across the doorsill where the two worlds touch.”

As Rumi said: “The door is round and open. Don’t go back to sleep.”

Annelieke Verkerk is a leadership, team and organisational coach and facilitator with a background in Systemic Work and Human Potential Development in The Netherlands. She has a Master’s Degree in Public & Private Law at the University of Groningen and 15 years experience with the Dutch government in staff and high-level leadership positions. She also has 18+ years of experience and education in consultancy, coaching, facilitation, teaching and mentoring.

Her work is currently focused on: Team & Organisational Coaching and Consulting; Systemic Constellation on Environmental & Societal Issues; Conscious, Embodied & Regenerative Leadership; Systemic Work and Public Speaking. She loves dancing, also with the paradoxes of life.

anneliekeverkerk@gmail.com

https://www.linkedin.com/in/anneliekeverkerk

Working With the Collective

Those who left and the Left Behind: A Liminal Space

Nikki Mackay

Those who left are also left behind, and those left behind have also left. The pain of this entanglement, and the wounds inflicted by it, pass from generation to generation; morphing, growing, and mutating with each iteration. It encompasses migration trauma, war trauma, and the fracturing of families. It is bound up with the fragility of safety, love, hopes, and dreams – the fragility of life itself.

Those who left are also left behind, as part of their heart stays with who and what they have left behind – those they love, their home, the life and dreams that they have lived and tended. And those left behind have also left because part of them goes with those who have left and part of them goes to the memory of ‘what was’ in this place that they now find themselves.

It is an immense pain, a ragged wound that splits souls and hearts open. It can define families, communities, countries – it can define a generation. The lost youth of WWI, those boys and men who left and are also left behind. Bodies in the ground in the battlefields and hearts left at home with the world that once was. The mothers, fathers, siblings, lovers, grandparents left behind and who also left their present, to have their hearts travel with those they have lost and into that past that existed before the ripping apart.

It is the moment for many when peace dies, when safety dies – and for some, when their beliefs and their relationship with God dies. Belonging and sense of place is also lost when grief cannot be formed and given a place. So often the grief cannot be given a place because of the very vastness of what is lost between the separate but inextricably linked those who left and the left behind.

The seeing and not seeing of pain and trauma, the actual cost of seeing and sitting with the pain and the ungrieved grief, is immense. It is in this space that the fears of our ancestors collapse into our own – the remembering of our ancestors’ pain and ungrieved grief in our own present grief and pain. It is exhausting this weight of seeing and not seeing.

The images of war-torn Ukraine, the women and children being pressed on to trains, kissing goodbye to their partners, brothers, sons. The seeing of these scenes and the unfolding conflict collapses us into the past. Parts of us can begin to view the present through our ancestors’ past.

Many times in constellation sessions I have used the phrase: “This isn’t then,” to separate out the past from the present story or experience. It is harder to access the separation and acknowledge the shift that usually comes with the use of that phrase in these present times. Because in many ways this does feel like then.

Exploring Collective Memories and Untold Stories

Since 2016 I have been working with Prof. K.M. Fierke, researching the effect of unacknowledged collective traumatic memory on present-day politics and conflict. In 2020, at the start of the pandemic, we were supported by the Human Family Unity Foundation to expand our research. Our initial focus was on exploring the legacy of empire on present-day politics, in part through the lens of the pandemic.

Topics explored have ranged from the European refugee crisis, the normalisation of the politics of hate, the impact of past memories of collective trauma showing up as influence on and effect of Brexit, climate change response, the pandemic itself, and many others. All of the constellation mapping is conducted blind. The results have been interesting and encouraging, regarding the potential for constellation as a tool in this arena.

What our findings have also highlighted, repeatedly in map after map, is the significance of the unacknowledged dead, ungrieved grief, and of unacknowledged guilt. Those three aspects appear time and again in the collective context. It shouldn’t be a surprise as constellation facilitators see it every day within the individual and family context.

Grief, Guilt, and the Dead

Ungrieved grief is not a benign phenomenon, and if left ungrieved and unmet, it morphs into unacknowledged guilt. The unacknowledged dead remain displaced and unseen. The prevalence of ungrieved grief in the collective context is incomprehensibly large – the need to not see, not remember, not feel, to numb out grief and pain. And yet the numbing out leads us on to guilt and unacknowledged guilt. The legacy of this guilt becomes an unwanted inheritance for the next generation. The guilt of surviving when others did not is passed down to, and placed upon, the children. Not only that, when we have these three root aspects of unacknowledged guilt, ungrieved grief, and unacknowledged dead entangled together, it creates the need for safety outside of seeing, witnessing, knowing and feeling. The ungrieved grief becomes exacerbated and a perpetrator response, a war narrative, comes in as a ‘false safety’ and it is indeed a false safety.

Bringing in a representative space for safety or peace in a constellation map can be a provocative act within the informing field, particularly within a collective memory constellation, because it is subjective. Safety within the boundaries of entanglements is not universal. Safety and peace for one representative may mean the exact opposite for the other. So what can we bring in to support a compassionate response, an aspect of seeing that is not a war narrative or perpetrator response within the field? We can bring in ‘tending the future of children’, a seeing of the children and the generations yet to come. That is the closest to a universal safety that we have found.

The ability to have a compassionate response in the present moment when we are surrounded by ancestral experiences, or the lived and present reality, of those who left/are left behind and those left behind/have left is directly linked to our own ability to see that painful wound within our individual, family, community, and cultural fields. It is no small thing. I have walked with this many times and the wounds are deep and entrenched.

Untold Stories from Ukraine

In December 2019, as part of a project with the HFU Foundation and Chris Halas Wood, to explore the roots of racism within the USA, we facilitated a series of group constellations exploring the legacy of migration trauma within the USA.

There was a significant number of attendees who were the descendants of Ukrainian and Russian ancestors. Over the course of our time together we set up several constellation maps to uncover and acknowledge migration trauma entanglements.

One of the participants, Sara, shared the story of her Grandmother, Rebecca. As a young newly-wedded woman, Rebecca left the Ukraine to go to the US with her Ukrainian husband at the beginning of WWI. Before she left, her mother made her promise that she would return to Ukraine after she had made a home for herself in the US. She went back to Ukraine to fulfil that promise to her mother and then returned to the US again. Her husband returned with her but refused to leave Ukraine again. Rebecca returned to the US leaving them behind and her mother and husband were murdered in the Babyn Yar [1] massacre during WWII. Rebecca had eight siblings. She managed to persuade some of them to leave for safety in the US but four stayed behind. The resulting constellation revealed entanglements that are still alive today in the present conflict, and they epitomise the deep wound that is those who left/are left behind and those left behind/have left.

Representatives included:

Sara

Descendants in the present

Rebecca

Rebecca’s Mother

Rebecca’s Father

Ukraine

Rebecca’s Husband

Promise to go back to Ukraine

Land in US

Those left behind

Persecution

Those that didn’t survive

Children

Belonging

Murder

Rebecca’s maternal ancestors

Rebecca’s paternal ancestors

The Dead

Safety

A different belonging

Silence

Debt

The representative for Ukraine immediately stepped out to the edges of the constellation space – isolated, observing and silent.

Persecution looked at Descendants in the present, becoming fixated on them.

Rebecca’s parents looked away from this interaction, they could not bear to see the Descendants in the present. This is a common entanglement present in war and conflict trauma. The weight of what was lost and the entanglements of those who left and those left behind can render an inability, or refusal to see the continuation of a lineage.

Rebecca’s mother described feeling that she didn’t know where she belonged; she had lost a sense of herself.

Persecution and Murder gradually became drawn to one another, moving slowly.

Ukraine became angry and agitated as the constellation unfolded.

The representatives for Children were drawn towards the Ukraine representative but Ukraine couldn’t see them. This is a collective example of the wound of the ‘those who left and those left behind’ entanglement.

The ancestors stood behind Rebecca’s mother, and they could see the Descendants in the present. However, they were more aware of Perpetration. They weren’t connected to Rebecca, exacerbating the sense of displacement within her.

Rebecca’s father was detached from his ancestors and was feeling sad and angry. The ancestors said to him: “I don’t want to be here” and at this point, Those that didn’t survive lay down. This was an indication of entanglements with the unacknowledged dead and unacknowledged guilt within Rebecca’s paternal line. It was a fractured line. A further representative for The Dead was added to lie down beside Those that didn’t survive, as the weight of the presence there was so great. Ukraine was drawn to them, as was Persecution.

Those that didn’t survive being seen by both Ukraine and Persecution was frightening for the representatives of Those left behind and they said:

“I am trying to hide. Don’t look for me. Don’t remember.”

At this point a defensive cluster formed, comprising of:

Ukraine

Promise to go back to the Ukraine

Rebecca

The Dead

Those that didn’t survive

The representatives for the Descendants in the present felt guilty and disconnected because of the weight of the ungrieved grief in the field. They spoke from the weight of that entanglement and the carrying of unacknowledged guilt within them was clear:

“I am guilty. I survived. It is hard to look at you. I believed it would kill me.”

Rebecca’s mother cried at this movement and a little of the grief began to shift.

This allowed the representative for Belonging to move to stand behind the representatives for the Descendants in the present. This was a significant shift and a supportive one – when this fracturing entanglement is held tightly, belonging for the Descendants in the present can often only be found through a connection with the unacknowledged dead.

A representative was added for Safety at this point. This created a movement with Rebecca’s mother. She began to look towards and see Those left behind and Ukraine. She also began to feel resentment towards her husband, describing him as being in the way of her being able to see Those left behind – an indication of the subjective nature of safety even within an individual context.

It became clear that from the perspective of Rebecca’s mother, Those left behind were her first loyalty – a promise made to her own lineage before the relationship with her husband. She had left her home in Eastern Ukraine to be with her husband in the West. Rebecca had been carrying that loss and fracture for her.

Rebecca’s mother was eventually able to say to Those left behind:

“I didn’t want to leave you. Part of me stayed. You have my heart. You were my first promise.”

A representative was then placed for A different belonging and that eased the entangled connection with Ukraine and Those left behind. Rebecca’s maternal ancestors were full of regret for not getting out sooner.

Rebecca’s mother spoke from the entangled grief saying:

“This killed me. This wasn’t love. This killed me.”

There was a significant emotional release for Rebecca’s mother in being able to break her silence. The representative for the Promise to go back to the Ukraine that Rebecca made to her mother gravitated towards Rebecca’s mother, further indicating that the promise originated with her mother and not Rebecca – it was an inheritance.

Those left behind began to move towards the representative for A different belonging. This provoked Silence to move towards the Children and block them.

No one is seeing the Children or the Descendants in the present at this point. The field is isolated and fractured with the weight of the silence and the broken promises. The safety included within the constellation map is not safety for everyone.

When the inclusion of Safety provokes a movement into not seeing of Children it is an indication that death is being held as an aspect of safety. A belief that death is perhaps the only safety and survival is untenable. This leaves deep marks on the descendants for many generations as they unconsciously believe that their very lives are a betrayal.

The Constellation Field was split into different entangled loyalties. Rebecca’s father was entangled with the Ukraine representative and the land there. And Rebecca’s mother was entangled with Those left behind, relating to her land of origin, and her first promise.

At this point, Rebecca’s mother could see and connect with the dead but there was an anger between them:

“I hate you. I blame you. I don’t want to see you.”

There was no compassion present and a perpetration narrative emerged instead as a false safety. The anger expressed in this context indicated an inherited belief that Rebecca’s mother was responsible for holding the unlived years and fulfilling the unlived dreams of the unacknowledged dead.

Rebecca was confused by the expressions of anger and felt trapped by her mother; she too was tethered to the ancestral broken promises. She faced her mother:

“I did this for you. Please see me. Please love me.”

The Descendants in the present moved to witness the exchange. It created a further movement within the Mother who described the terrible things happening around her and that she needed to choose that:

“You have to keep the promise. I can’t love you. It isn’t safe.”

She then repeated to her husband:

“I can’t love you. It isn’t safe. My heart has already died.”

This is another common entanglement in migration trauma and the descendants that come from it, epitomised by an internalised inherited belief that love is dangerous and often tainted. It is incredibly painful and leaves wounds on subsequent generations.

The representative for Perpetration was emboldened by the naming of the entangled belief by Rebecca’s mother, and moved towards Those left behind stating:

“I own you.”

Those left behind replied:

“I’ll kill you.”

There was a disturbing enslavement pattern here with an inability to see the dead or the children. That pattern was holding both Perpetration and Those left behind within the entanglement. The representative for Murder then wrapped their arms around Those left behind. There was a struggle between them. Those that didn’t survive and the Dead were pushed further away, becoming more unseen, as Perpetration, Those left behind and Murder stayed in a perpetration dynamic within the historical narrative of war. This is a false safety and there is a deep cost to it.

Those that didn’t survive were physically moved to Those left behind in an effort to shift the Field out of the ‘war as safety’ narrative, and for the Dead to be seen. Unfortunately, there was still a refusal to see the Dead. Perpetration began to see the Children but tried to deny their place:

“When I look at you it costs too much. You can’t be children. You can’t be innocent.”

They were looking at the children through the unacknowledged dead, unacknowledged guilt, and the ungrieved grief.

The Children said:

“I am children. I am innocent. I existed. I lived. I breathed. I lived. I died.”

The representatives for the Children then repeated this to the rest of the created constellation space.

Rebecca’s mother became agitated by this:

“I hear them. I can’t love you. It costs too much.”

This again, is the entanglement with the unacknowledged dead, unacknowledged guilt, and the ungrieved grief. The Descendants in the present, however, gradually shifted and were able to see and to say to the Children:

“I see you. I have lived you. Part of me comes from you. I feel you waiting to be seen and loved. I have been waiting with you. I believed I had to be you. I am not you but I can see you.”

This provoked a significant shift and relaxation in the Field. The Children began to be seen and the Descendants experienced the beginnings of a shift within their belonging. The sacrifice of the children was held as a silent secret and the lack of safety in love, what love means, and the children’s suffering of the trauma is the inheritance at play in the present descendants. It is underpinned by the weight of the unacknowledged dead, unacknowledged guilt, and the ungrieved grief.

This movement allowed the Descendants to release themselves from the Ancestors who were still waiting for their dreams to be fulfilled. A lineage of women from present generation to five generations back were able to release the broken promises and see one another. However, the Ukraine representative was still deeply agitated. The Children were seen but the Dead, and Those that did not survive, were still not seen and Those left behind were still very active. From the Descendants in the present’s perspective, enough had moved to allow them to begin to face their future:

“There is more than death here. I can choose to live.”

The individual intersected with the collective here, and only the individual context shifted. The historical narrative of the original promises that were linked to land, war, and fracturing remained. There were indications within the map, of influences from inherited political loyalties for Ukraine and between Ukraine and Russia/Poland.

Collective Inheritance of Contracts, Secrets, and Betrayals

We explored this collective aspect further in a subsequent constellation and there were some deeply entangled roots. This was particularly active around the cost of the Russian Draft (conscription was compulsory for all males over 21 and was for a period of years) and the avoidance of it, an added collective weight of guilt between Those who left and Those left behind.

The increased presence of perpetration within the map was striking. The representative for the Draft slowly moved towards Those who left, saying:

“I own you, I own your guilt, I don’t care whose blood, I just want blood.”

This lack of compassionate response indicated a deeper conflict and perpetration entanglement around betrayal and broken promises. It continued when Those who avoided the Draft said:

“No. I am not coming back.”

The Draft responded with:

“I already have you.

I own you.

You owe me.

You owe me blood.

I just want the blood.”

This was disturbing and emotive within the map. There was significant tension within all represented spaces and it was another indication of entangled broken promises between Ukraine and Russia.

Those who avoided the Draft then said:

“I’m not coming back.

You can’t have me.

You can’t have my children.”

The Draft responded with:

“I already own your children.”

Another representative for Those who avoided the draft became very distressed by this, stating they were worried that the words spoken by the Draft were true and that they never actually escaped. This is an aspect of an entanglement around the cost of survival – the weight of the unacknowledged guilt, grief, and dead that is passed to the children when it is unseen in the present – a toxic legacy.

A representative for Debt spoke to the Draft:

“Forget me. I want you to forget my promise.”

This is an older entanglement of broken promises speaking but the Draft refused to acknowledge it. The Descendants in the present were very distressed and displaced by this. Similar to Rebecca’s mother in the earlier map, they were drawn to the Dead and the weight of the guilt and ungrieved grief.

“I’ve lost my place.

I don’t know who I am.

I can’t remember who I am.

I can’t remember my name.

I can’t remember my land.

I can’t remember who I am.”

The Draft representative was satisfied and comforted by this. The perpetration response as a false safety was active. They stated:

“You owe me this.”

Then to Those who left:

“I’ll take them instead.”

The representative for Guilt stated that they wished they had chosen death rather than this. The cost of survival was huge here and there was a fracture between Those who left and Those left behind that is complicated by the historical narrative of the broken promise between Ukraine and Russia that existed before this draft.

Those Left Behind said to Those Who Left:

“I need your life to be my life. I claim it.”

This is clearly an entanglement holding both aspects in a liminal space. The need for safety through perpetration was entrenched within the map and appeared, again, to be older than the draft.

The Draft shifted at this point to say to Those left behind:

“They left you.”

This changed the Field and Those left behind began to weep; the grief was finally breaking open. The Draft saw this grief response and softened a little:

“Your grief is like my grief. Your dead are with my dead.”

This movement created a place for grief where it had previously been denied.

However, Those who couldn’t avoid the draft were still stuck within the actual avoidance of it, the contract was still active for them and their descendants. They were able to break the guilty silence and secrecy around this and say:

“I didn’t agree to beyond this life.

I didn’t agree to forever.

I didn’t agree to my children taking my place.

I didn’t agree to give you my soul.

My soul is my own.

You’ve stolen my soul – I want it back.”

This shifted the focus to Those who left and the Descendants in the present.

The weight of the guilt was overwhelming for the Descendants in the present and in spite of the ancestors of both Those who left and Those left behind saying:

“Please live. Please live,” they found it very difficult to separate and take their place. They were holding the weight of the unacknowledged dead, guilt, and grief from the original root entanglement and trauma. It was only when Secrets stood with Descendants in the present that they could move away. This was a release, but it did not clear the root collective entanglement.

The constellation was stopped at this point after supporting the representatives for Descendants in the present to drop into the individual Field and say:

“I am going to live. I am alive now.”

A Lived Legacy

This pain and grief is in each one of us as we witness – or not – the present unfolding trauma in Afghanistan, Yemen, Ukraine and others. As we find ourselves in the midst of the ‘cost of living crisis’, scarcity fears, the deep uncertainty of climate change and of war, we are plunged into the entanglements of our ancestors. And not only that, we feel their rip away from safety at moments in our own lives when we lose, or prepare to lose, safety. When a loved one dies, a relationship ends, a dream is lost, we embody that fracture of those who left/are left behind and those left behind/have left. Sometimes we hold it internally within our souls. The rip between who we were before and who we are after trauma. The parts of ourselves that we leave behind with what we lost and the attempt to numb out the part of us that stays, trying to find a solid footing in a world that is not the same as the one we have lost.

We need to tend this sacred wound of those who left/are left behind and those left behind/have left because it is being laid bare in our collective. Our world is changing in big and little ways and the ghosts of the ancestors’ untold stories have been stirred. It costs a lot to grieve this wound but it costs more not to. And if we don’t tend the wound, instead of tending a future for our children we are leaving them the continued unwanted inheritance of unmet grief, unacknowledged guilt, and unacknowledged dead.

We are living through a period of time that will be remembered in history. It is imperative to tend the grief, pain, guilt, loss, and trauma that is happening now. We know more today about transgenerational inheritance of trauma than our ancestors did. Our ancestors could not stop and had to keep going to survive. We are therefore still knowingly or unknowingly living their untended wounds. We can break the pattern of inherited trauma by choosing to pause, feel and witness what is, as it moves through each one of us.

I have been working with the ache of this around my own responses to the world we are currently living in, as well as with clients and groups. Sitting with the spaces of the unacknowledged dead, ungrieved grief and unacknowledged guilt along with a space for tending the future of children, is a small offering.

I work with speaking the following phrases to all those spaces:

Your pain matters

Your grief matters

Your beliefs matter

Your love matters

Your lives matter

Your children matter

Your dreams matter

Your hopes matter

What you have lost matters

I see you, and I am not the only one

I am grieving, and I am not the only one

The grief has a place and there is more than grief

This doesn’t have to become then.

Stopping, pausing, breathing into the pain, grief, and loss – sitting with it – is important. This is the medicine. If we do not do this then the children, the next generations, will have to do it for us.

Note:

1. Babyn Yar – also known as Babi Yar – is one of the largest World War Two mass graves in Europe. The massacre of 33,771 Jews at the ravine on the outskirts of Kyiv took place over two days in September 1941. As the Holocaust continued, German forces continued to perpetrate crimes at Babyn Yar, using it as a mass grave to dispose of up to 100,000 bodies, until the Soviets took control of Kyiv again in 1943. As well as Jews, Roma, Ukrainian civilians and Soviet prisoners of war were also murdered there.

REFERENCES

Boccagni, P. (2015) Emotions on the Move: Mapping the Emergent Field of Emotion and Migration. Emotion, Space and Society, Stockholm, Sweden.

Fierke, K.M. & Mackay, N. (2020) To See is to Break an Entanglement: Quantum Measurement, Trauma and Security. Security Dialogue, Ottawa, Canada.

Hellinger, B. (2003) Farewell: Family Constellations with Descendants of Victims and Perpetrators. Carl-Auer-Systeme-Verlag, Heidelberg, Germany.

Berkhoff, K.C. (2008) Babi Yar Massacre. The Shoah in Ukraine: History, Testimony, Memorialization, Indiana University Press, Indiana, USA.

Mackay, N. (2020) Your Invisible Inheritance, Rebel Magic Books, London, UK.

Marchetti-Mercer, M. (2012) Those Easily Forgotten: The Impact of Emigration on Those Left Behind. Family Process, Philadelphia, USA.

Sanborn, J. (1997) Conscription, Correspondence, and Politics in Late Imperial Russia. Russian History, Leiden, Netherlands.

Nikki Mackay (BSc, MSc) is a Family & Ancestral Constellation therapist and teacher. She previously worked as a Clinical Physicist within the NHS, specialising in Neurophysiological measurement and exploring the efficacy of energy healing on the autonomic nervous system. She has a busy therapy practice and teaching school. Since 2016 she has been researching the possibilities of constellations at a macro level, working with the International Relations Department of a University in Scotland, looking at using constellations as a tool for understanding collective memory and trauma. Her fifth book: ‘Your Invisible Inheritance’ was published by Rebel Magic Books in May 2020.

nikki@nikkimackay.co.uk

www.nikkimackay.co.uk

www.facebook.com/ConstellationConversations

Advertisement

History of Nations, Cultures & Religions

In Solidarity

Veronica Bañuelos Miramontes

I am the daughter of Silvia Miramontes Mercado and Fructuoso Bañuelos Cabral. My grandparents are Jesus Miramontes and Albina Mercado from my mother’s side and Fructuoso Bañuelos and Maria Cabral from my father’s side. My family’s indigenous land is Zacatecas México, north central part of the country. Unfortunately, this land is currently one of the most violent states in México due to drug cartels fighting for territory in order to transport drugs into the US.

I identify as Chicana-Mexicana. Chicana is an identity that speaks precisely to the nuances and challenges of having been born in the US and of indigenous lineage.

I was encouraged to contribute to The Knowing Field by Francesca Mason Boring. I must admit that I was intimidated by this invitation and froze! Yet spirit kept thawing me out and encouraging me to write as well. This is my first contribution to The Knowing Field.

My name is Veronica Bañuelos Miramontes. I am a 47-year-old Chicana-Mexicana living in Portland, Oregon. I am an independent consultant focused on interracial and intercultural conflict in the workplace. I am a social scientist by heart and a systems thinker by training. I had a spiritual calling early in my life, yet, because I was born a girl in a heavily catholic culture, I was not able to pursue nor consider priesthood. I found other ways to fill my spiritual cup, including spiritual directorship training. The work that I do now also feels like a calling and a highly spiritual practice. I am grateful and honoured by it.

My professional studies are a reflection of both my personal and professional purpose. Human Development provided the foundation of theories and practices of communications, interpersonal skills, psychology and sociology. And my graduate programmes in Management and Organisational Leadership informed my systems thinking approach in organisational conflict, and leadership theory of development.

But it was my beloved mediation teacher Renee Bové who I trained with after graduate school, who indirectly introduced me to constellations. I felt, sensed and witnessed Renee was above and beyond any other mediation teacher. I had had other mediation teachers, yet what she brought to the table was profound and her approach went deeper than a mediation process. It was the framework of constellations that allowed her to reach for people across the systemic layers. This approach felt holistic and I was hooked.

Years later, Renee introduced me to Jane Peterson. Jane became my first ‘official’ organisational constellations teacher, and I continue to learn from her today, as well as from Leslie Nipps, and of course Francesca Mason Boring. I consider all of these women my elders and I am grateful to each of them.

I have been learning and training in constellations for the last three years. In that time, I have learned that the constellation community also struggles with understanding and healing racial divides. I have to admit that I was surprised to learn that the constellation community struggles with the same exact racial conflicts and disconnections as the wider world. I suppose I wrongly assumed that systemic thinkers would be a bit more immune to the racial discomfort/strife, and it is through this lens of racial conflict that I focus my first writing, while prefacing that this is only my perspective and it in no way encompasses the experience nor understanding of all BIPOC folks (Black Indigenous and People of Colour).

I often hear from white folks, how hard it is to reach and connect with BIPOC folks. A common question I hear is: “What can I do to get more BIPOC into my field, my organisation, class, network, groups, relationships etc.?”

The answer to this question is complex and I will start to address this question by sharing a story.

Last year a beloved friend had a beautiful baby girl. This friend is one of a close-knit group of indigenous women who I consider sisters. Our friendship group was delighted to have a new member in our lives.

Days after the delivery, we learned about some congenital challenges. The baby was born with a curve in her spine and a malformed skull. She had to go through painful daily stretches, which agonised both mom and baby. She also was to wear a clunky hard-shell forming helmet, day and night.

Our dear friend shared with us her angst as she tearfully explained the painful process she had to put her daughter through and explained how strenuous it was for both of them. We supported her the best we could and made a plan to visit in the next month.

The day finally came. A group of eight indigenous women came to visit mom and daughter.

There we were around the dining table. The baby (eight months old now) with her helmet on, was being passed around from arm to arm. With each pass, the women would say the same thing: “She is so beautiful; or “She is heavy”; or “How much does she weigh?” “How was your delivery?” Yet, no one made mention of her helmet or asked about her spine. It was too uncomfortable for them to bring up.

I noticed the baby would try to look into each woman’s eyes, trying to make a connection, but they were not looking back. The women were talking about the baby but not with her. They would quickly turn her around and sit her on their lap and converse with the group. The adults were not engaging with the baby as a person. I noticed the baby began to get distressed and started to cry.

I took her next…

I sat her on the table and I was sitting on a chair. Our eyes were at the same level now. I held her eyes and decided to simply witness her, I simply smiled and said: “Hi….” She stared into my eyes with a flat affect for a really long time, just staring. I felt her pain in my body; she was showing me all of her pain in that deep, penetrating gaze. It was difficult, but I committed to staying with her eyes. She kept looking deep into my eyes. The longer she stared, the more impotent and distressed I felt. Feelings of injustice, anger and sadness came over me. My heart began to break for her and with her. My eyes welled up. I am glad all the women were engaged in conversation with each other; this was a special moment between just baby and me.

After a long while, I believe the baby finally felt met and seen. She got comfortable enough to get curious about looking out into the group. She began to turn her head and only then did I sit her on my lap. Now we were curious about the rest of the group, but we were still connected. As others wanted to take her, she made sure it was known that she was not interested in leaving my lap! Of course, this brought me joy! We bonded that day and ever since she trusts me to see her as a person.

It is important for me to say that the rest of the women care for this child as much as I do. The only difference is that it was too painful for them to sit with the impotence and share in the physical pain of this child. It was easier to ignore and turn away from the pain.

I decided to be an ally to this baby, because I saw her struggle. I had to be willing to hold her in her full emotions and just be present first, before she could trust me and feel safe.

The question I would like to ask those of you who wonder about what to do and how to address racial disconnection is: Can you fully see me and hold me in my pain? Can you see and hold us BIPOC folks in our pain? Can you see into the depths of our transgenerational trauma of colonisation, war, slavery and attempted genocide? Can you see and sit with us and hold the truth of the disconnection from the land and each other as a result of colonisation? Can you hold us in our full emotions of rage, anger and sadness? Can you just feel us, and witness us, and see us first?

In Bert Hellinger’s Love’s Hidden Symmetry, Chapter on Seeing. Pages 206 and 207:

“If I succeed in truly seeing someone, then I’m in contact with something greater than either of us alone. My immediate goal can’t even be to help, but only to see the person in the context of a larger order. That’s how seeing works, and it allows therapeutic interventions to remain respectful and loving, while at the same time being a force for healing.”

I often have a sense of fear and trembling about seeing, but if I shy away from what I see, if I hold back – even out of the fear of hurting someone – something closes down in my soul, as if I abused something precious.

I invite you to be present with BIPOC folks and hold their full humanity (fear, rage and all) while standing in your own full humanity (fear, rage and all).

Can you be an ally?

An ally is someone whose personal commitment to fighting oppression and prejudice is reflected in their willingness to:

Educate oneself about different identities and experiences

Challenge one’s own fear, discomfort and prejudices

Learn and practice the skills of being an ally

Take action to create interpersonal, societal and institutional change

I know the shame and pain that many white folks feel for the actions of their ancestors. Slavery, colonisation and attempted genocide are part of their story.

This is hard to sit with, and look at. So instead, many white folks just pretend the spine is not curved and the helmet is not there. They can’t look in our eyes and hold us in our full emotion. They can’t take us in. We sense this and want to turn away, reinforcing the original hurt of disconnection.

A pearl of wisdom that I learned in constellation theory is that rage is repressed life energy. I certainly see rage, anger and sadness in my work a lot and I include them as part of the holistic and systemic seeing.

One of my favourite questions to ask in white affinity groups is: “How has racism impacted you? What have you lost?” White folks don’t tend to think about the cost of racism to themselves. In my experience I have learned their loss is disconnection from us, (the people of the global majority) and a disconnection from themselves that comes from looking away and numbing.

What I see now is the weight of the collective trauma that has continued to be repressed. I understand that the numbing can come from the history of the white ancestors. I know now there is shame, anger and rage here too.

What is required from white allies now is to include and reconcile with the history of the ancestors in their role of oppression of BIPOC folks. I believe that as diverse systemic constellation thinkers and processors, we are uniquely situated to hold all of the pain of the past with systemic understanding and love for our collective healing.

Veronica Bañuelos is a bilingual / bicultural Chicana focused on Holistic Organisational Development and Intercultural Communications. As an independent consultant she spends her energy supporting people and organisations to move closer to their mission and each other through supportive communication and relationship building as executive coach, mediator and trainer. Her professional studies are a reflection of both her personal interests and life purpose. Her undergraduate degree work in Human Development provided the foundation of theories and practices of communications, interpersonal skills, psychology and sociology. Veronica’s graduate degree in Management and Organisational Leadership from Warner Pacific University informed her leadership theory of development, operations, and dynamics of an organisation, which is also supported by her Certificate of Financial Success for Nonprofits from Cornell University in 2018.

Advertisement

History of Nations, Cultures & Religions

Voiceless Women – An Unspoken Legacy

Nikki Mackay

Women’s stories and contributions are often unacknowledged, unseen, and silenced. The missing voices and stories become an all too familiar part of the everyday landscape, passing quietly from one generation to the next. In the familiarity of this silent landscape, the missing pieces can go unnoticed and unquestioned. That doesn’t mean that those pieces don’t exist or are benign.

Those women who came before in the family and ancestral field have shaped those that come after. Those that were the first in the lineage to do or experience certain things, willingly or unwillingly, have left a particular imprint. The first to marry for love, to divorce, the first to choose to study and have a career, when that simply wasn’t what was done. The first to travel, to follow a different belief, the first to vote, to own land and property in their own name – they will all be there in the family and ancestral field. The brave and courageous women who carved their own paths and went their own way, despite perhaps tremendous pressure and a great cost to do otherwise. Those are exciting, inspiring, and exhilarating stories that often remain untold or are reduced to a short couple of sentences about what a ‘pistol’ a particular ancestor was, or how stubborn and difficult she had been.

What of the other women? Those who were rendered voiceless within their own lifetimes, who found themselves married off without any attention paid to whether it was their heart’s desire or not. Or those who were relegated to ‘spinsterhood’ by the cultural conditioning. The women whose dreams of learning, creating, travelling, working, were quashed by the weight of expectations of being the ‘good daughter’, the ‘good sister’, the ‘good wife’, the ‘good mother’. Women trapped in abusive situations, women who lost their homes, their dreams, their safety, and their ability to say ‘No’. Those who did their best to survive it, even if that meant hardening their hearts and trying not to feel. That takes courage too, but those stories are even more silenced, unlikely to be mentioned at family gatherings or in any other place. The women who grew brittle and bitter as life and the times they lived in rendered them ghosts whilst they were still alive. The reluctant brides, the widows, the ‘old maids’, the would-be authors, the would-be travellers, doctors, farmers. The weight of crushing disappointment and oppressive ‘choices’, the cost of conforming and the cost of not.

This vast spectrum of voiceless female experience informs the descendants in the present in many different ways. Although we do not yet live in a world where all is equal for all genders in all places, it is significantly better today than it was for our ancestors. The freedom to choose is far greater today than it was then. And yet the lens of the oppressiveness of that old world is still one that individuals can each see or be seen through today.

When I work with individuals or groups to explore the stories of the women in their family and ancestral field, there can be a romanticised notion of what the experience will be like. Of perhaps uncovering a lesser-known branch of their family tree where there will be a sense of kindredness and ‘coming home’, a resonance of spirit and soul. Of course, that does actually happen, but the journey from here to there involves sitting with the stories and people that are known as well as those that are unknown. The legacy of these voiceless women has been permeating through lineages for generation upon generation. Some of those souls are wounded, scarred, prickly, and often haunted by their own ghosts. The legacy of such wounded ghosts is the creation of more wounded and scarred souls. The wounded people in the family field have been entangled with the costs of the previous generations being rendered voiceless and unseen. The pain is real and it is lived generationally. This means that the first brush with the voiceless legacy of the unseen women in an individual’s lineage and field most likely will be through the painful relationships in the generations that are closest to them, because we are each still living the unacknowledged trauma of these women and it is no small wound.

The mother, grandmother, great aunts, who were bitter, who withheld their love and spread numbness or pain, is as much a legacy of the voicelessness placed on the women in the influent field as the unknown heroine who struck out on her own, defying all odds. The quiet gentle great-grandmother who was encumbered with an alcoholic partner, and ‘made do and mended’ in poverty for her entire lifetime is as much a legacy as the woman who fought the system to go to university and became a doctor. Both paths require immense fortitude, sacrifice, and grace.

We can be as bound to seeing our ancestors through the ‘good girl’ lens as we are impacted by it ourselves – consciously or unconsciously drawn to the ‘good ancestors’, the ‘good women’ rather than the bitter, cold, wounded souls. It is hard to sit with someone else’s pain, particularly when it has been unmet by them or those around them, when it has morphed into bitterness, sometimes vindictiveness, and downright nastiness. Behind that unmet pain is unmet and ungrieved grief, and behind that is a story yet to be told – not an excuse but a story.

The Making of Scarlet Women

A tool for control in any system is shame and blame. The cost of stepping outside of the cultural rules in the community or family we live in is high. This legacy of shame and blame runs through every family and ancestral system. Even that choice to explore, to see what is there, can be a provocative one and go against the beliefs and agreements that run through the structure of a family system.

Those designated as ‘Scarlet women’ are women who act or speak outside of the system that they live in, whether that is family or cultural. The scarlet women entanglement comes in as the cost of not being the ‘good girl’. In the past, ‘Scarlet women’ were defined as sinful, promiscuous, or immoral. Things that happen today that are commonplace, such as divorce, having a baby when unmarried, abortion, speaking out against injustice and violence, saying no to things, saying yes to things, choosing a certain type of career, would have resulted in huge consequences for the ancestors. It would also bring in the legacy of the ‘scarlet woman entanglement’.

Mistakes are Sacred too

In many of the collective memory constellations involving this and other associated ‘good girl’ dynamics, voicelessness and the fear of breaking a silence plays a key role. This is the fear of the cost of being true to oneself. The great fear of being different, of being seen to be different. Where courage has been grasped to dare to be different, in whatever form that courageous choice takes, for the ancestors and the descendants, there is fear of what might happen next. Not only in the perceived cost of making the choice itself, and that if an individual dares to choose themselves they may find themselves rootless and cast out. No, the fear is much more than that. The fear comes in around a belief that they need to be perfect and get it right. Now that they have dared to be free, somehow they need to be more perfect than if they had stayed and conformed, submitted, capitulated to the ‘good girl’. The deep need to be perfect stems from a damaging inherited belief that safety is only to be found in ‘perfect’. This shows up in so many ways and it is a trap because perfect isn’t real. It is impossible. It is a prison where all those souls who dared to dream outside of the ‘good girl’ entanglement are in grave danger of ending up. In the stories I have stepped into with groups exploring this dynamic there are interesting words spoken from this entanglement. And they are repeated, in different stories, with different groups of people. When this repetition of a spoken entanglement happens, it points to a root pattern. The words spoken have been:

“I made a mistake. I got it wrong. Please don’t kill me.”

And the fear for those speaking is always palpable. Mistakes are believed to be a death sentence, because for some ancestors they were. The roots of this belief are full of shame, shunning, exclusion and perpetration. But who among us has lived a perfect life? I know I haven’t. I don’t think I have ever met anyone who has. It is not possible. However, the need to be ‘perfect’ if we dare to be seen and heard, or ‘good’ and submit to the agreements placed upon the ancestors, has become a lived legacy.

It also creates patterns whereby the women in the ancestral field have persecuted each other within the system of beliefs they live in. When I work with these stories there is of course the presence of the patriarchal system and cultural system, but there is also the need to survive at whatever cost that runs like a deep undercurrent through the stories. Women against women, entangled within the system, believing that their safety and worthiness of belonging comes from avoiding being shamed and blamed by placing that blame on someone else. Safety through perpetration and persecution. Safety through numbness. There are collective memories at different points in our history that illustrate this such as: the Persecution of Witches, the Magdalene Laundries, Collaborator Horizontal, amongst others.

This entanglement kicks in between mothers and their children. The mothers in the field of influence who cast out their pregnant or ‘different’ daughters, who shame their sons, who are running an internal belief that being ‘good’ is safer than love. This wounding response is a painful legacy that is ubiquitous in the field and its silenced roots are entrenched in the untold collective stories of the persecution of the feminine. It is why there can be such fear of making a mistake. It is the intersection of the ‘good girl entanglement’ and the ‘scarlet women’. The cost of the punishments placed on previous generations becomes the inheritance that the descendants live with.

Divorce and the Good Girl

Divorce is an interesting piece to work with when exploring collective memories. In western society over half of all marriages end in divorce and divorce is now generally thought of as commonplace. But it is a very recent phenomenon. It is only in the last few decades that it has been possible for women to petition for divorce; in certain faiths it was forbidden and would have been a devastating and shameful event for both families involved. The historical narrative of divorce trauma is why, even in cases of an amicable divorce, there is such a strong response to it from the surrounding family and ancestral fields.

The reasons for this strong field response to divorce are complex. Perhaps in some cases it is the first divorce in the family that has been petitioned by a woman. In previous generations this would have been impossible. Divorce would have been perceived as being dangerous, particularly for the woman, and the loss of name, land, place, and belonging can appear in the constellation with a pull to unseen, silent, excluded and forbidden women, with a resulting separation and exclusion from the family’s belief system. There may also be a narrative of punishment and shame flowing silently through the field of influence.

The usefulness and immediacy of effect of constellation in supporting individuals through the painful process of divorce always strikes me. I have worked with countless clients at various points of the separation and divorce journey and seen constellation transform something that has been crushing, excluding, and often intractable, into something more peaceful, with a space for resolution and belonging.

The impact and cost of divorce within the constellation setting, in terms of emotional belonging and freedom, is far greater on women than on men. I do not mean to say that divorce is easier on men than on women or that there isn’t an emotional cost to men. What I am saying is that within the invisible structure of our culture, society and families, the invisible ‘agreements’ relating to divorce and what it means to be a woman who chooses it or experiences it in any way is loaded with inherited legacies, agreements and beliefs.

Cost of divorce in the ancestral field

For many of our previous generations, a wife was considered the property of her husband in the UK, US, and Europe. She passed from the place as a child under the authority of a father or brother, to the place as a wife under the authority of her husband. This changed gradually but it took a long time. After divorce she could still not own property, even inherited property, earn money or have access to her children. She could not take back any property or wealth that she had entered the relationship with. Anything she earned would go back to her husband. It remained this way until 1887. This too gradually changed but there was significant stigma and it was not common for a divorced woman to be able to have a recognised subsequent relationship.

Men could divorce women, in 1857, before women could divorce men. They could divorce women for adultery and also have them institutionalised. Women needed adultery plus another action, such as desertion for two years or physical cruelty in order to instigate proceedings, and this was made very difficult. Divorce was mainly for the wealthy.

Even in the UK, before Independent Taxation was introduced in 1990, the income of a married woman living with her husband was treated for Income Tax purposes as his income and he was responsible for her tax. Today, the Catholic Church still refuses to acknowledge divorce in the spiritual sense. They believe that once you are married in the church, you are married forever.

The impact of this on the descendants is huge, particularly for women. Women in the present, in the throes of divorce, can find themselves cast out of their own sense of self, out of their very belonging. Friendships, family, and working relationships can change as the lens of the past comes into force. They can find themselves unseen for who they actually are and viewed with suspicion – an energetic return to the place of a child under the father or brother’s charge, which is a wholly disconcerting experience. There are obvious present generation and relationship dynamics to be worked with in a divorce constellation. However, it is imperative to consider the collective ancestral memories around it.

The loss of place, name, children, autonomy, property, wealth, reputation, and sometimes freedom for the ancestors translates to deep entanglements around the fear of such experiences in the descendants. This influences not just the woman who finds herself in the midst of divorce but also those around her, in all areas of her life. For her, love itself may become dangerous and tainted, from some of those around her. She herself has become the threat.

Ella’s Story

I explored the legacy of divorce in the ancestral field in a recent collective memory constellation group. The story we worked with was Ella Sinclair’s and her descendants in the present, who had also experienced a painful divorce from an abusive partner.

Ella was married to Alfred Sinclair and they had a young son together. Their marriage was happy until Alfred returned from serving in WWI. He returned a changed man. He was violent and abusive. He wanted out of the marriage and had begun to have an affair. Ella sought support from her own parents and her husband’s but she was advised to turn a blind eye.

Alfred started divorce proceedings against her. At that time, in 1925, Ella had very few rights. Divorce was not yet common and the power resided with the husbands. The divorce was petitioned citing Ella as mentally incompetent and an unfit mother. She lost access to her son and was institutionalised for a number of years. Her parents abandoned her, and her in-laws took Alfred and his new partner’s side in the unfolding events.

The constellation was set up to include:

Ella Sinclair

Alfred Sinclair

Ella’s parents

Alfred’s parents

Alfred’s new partner

Ella and Alfred’s son

Divorce

Descendants in the Present

Belonging

Love

Beliefs

There was so much silence and pain in this constellation. Alfred, who petitioned the divorce from Ella could only see himself and his own pain. He was unable to see outside of himself. There was also a significant amount of negative focus on Ella from all of the other representatives, particularly her parents. However, none was shown towards Alfred.

The descendants in the present also initially didn’t want to look at any of it and couldn’t bring themselves to engage with Ella. Ella described a huge sense of pain, shame, and grief. She felt as though she had failed. She didn’t feel comfortable or safe looking at the descendants.

The woman that Alfred went on to be with was also very perpetrating towards Ella and wanted her place.

“You don’t exist anymore. I am Mrs Sinclair.”

Both Alfred’s and Ella’s parents were numbed out with pain. Ella’s parents were ashamed of Ella. The cost to them and their family was perceived as too great and they would not acknowledge her existence. The divorce representative was full of rage and unmet grief.

Initially neither of the parents could see the descendants in the present either. However, after Ella spoke again of her pain, saying: “I failed. This is worse than death. Please don’t look at me,” there was a shift in the field.

After hearing Ella talk about her deep sense of failure and shame, the representative for the descendants in the present was moved to say to Ella:

“There were children. I am here because there were children. Your love still matters.”

This began the shift within the field and Alfred’s mother came forward out of the shadows of her own husband. She was now able to see the descendants and Ella. The mother described being in a prison-like state herself and having a compassionate response to Ella and the descendants in the present, but not knowing how to reach them. She wasn’t free to reach out to any of them until the phrase: “Your love still matters,” was spoken. This is a significant movement and is the beginning of the breaking of the belief that love is dangerous and in particular that the love from a ‘shamed’ woman is dangerous.

The field opened up further when Ella heard the descendants in the present talk about love. She was mesmerised when they spoke of mistakes being made and that they weren’t a death sentence or a prison anymore.

I have made mistakes and I am still worthy of love

I have made mistakes and I am still worthy of my life

I have made mistakes and I am still worthy of my children

There is a place for mistakes

The mistakes are sacred too

I am vulnerable

The vulnerability is not shameful

The realisation that the children were living a different life tended a wound within Ella.

In many divorce constellations there is a real and deep fear of being associated with the divorced or accused women, as if the shame of it all would be contagious. This undoubtedly has threads back to the ‘witch persecution’ memories and the persecution of the feminine.

Another significant entangled layer in this constellation was between the ‘imprisoned’ women – the mother-in-law who was imprisoned by her marriage and Ella who was physically institutionalised as well as trapped in the cost of marriage and divorce. This collective memory of mental, emotional, and often physical imprisonment or institutionalisation is a silent and insidious inherited wound. It was released within this map for both Ella and her mother-in-law when the descendants in the present were able to say that they had escaped their own abusive marriage.

I got out.

I refuse to go quietly into the unseen.

I refuse to go quietly into the voiceless.

You are no longer bound to them.

Your soul is free.

Death has taken the promises.

Death has taken the vows.

Death has taken the denouncement.

I know a different love.

I am here because there was more than death.

I know a different love.

I got out.

I am not running.

I am sitting with you in this place.

Grief has broken me open too.

I am sitting in the stillness.

And it isn’t death.

This not only soothed the ancestors, but it also soothed the descendants in the present. The fear, pain, shame, and grief are entangled. Along with the belief that there can only be one love, one choice of love and a lifetime of aloneness and punishment if it fails. Failure was a word with a big presence in this, and other divorce constellations. There was a deep sense of shameful failure associated with it that ‘belonged’ with the women, regardless of their actions. It was hard to sit with for many in the group, in part because it is so familiar.